People Care

Our communities are made up of people whose lives are intertwined with each other and caring for ourselves and one another is essential. What are the best ways to do this?

Burnout is common in those that work in Community Climate Action. In the “Minding Ourselves” webinar we look at why this is the case and how we can take better care of ourselves and each other in challenging situations. There are also comprehensive links to resources that might help.

Community Climate Action can bring many benefits – a sense of belonging and hope, good food, nature connection, support and creativity – and it is important to share these benefits with those that may not be naturally drawn to the cause. Bringing less often heard voices to the table can also bring huge benefits to your organisation. The “Engaging our Wider Communities” webinar brings together people from diverse backgrounds to share their experiences and some helpful resources are also provided. There are also case studies and data about the challenges and approaches taken by place based centres regarding social inclusion.

We look at the importance of celebrations to community groups and showcase Féile na nÚll – the yearly apple festival in Cloughjordan as inspiration about how, with just a few apple trees, you can create an engaging community event with a broad appeal.

Minding Ourselves

Why is it that people working in Climate Action are at high risk of burnout and what can be done about it?

Join Chris Chapman, Lead Facilitator at Burren College of Art, in conversation with Luea Ritter, a co-founder of Collective Transitions – an international action research organisation dedicated to building shared capacities for transformational shifts. Recently, Luea was at COP28 working for the Youth Negotiators Academy providing training and support for youth representatives.

Questions they will be addressing include:

- Why might people working in climate action be at particular risk of burnout ?

- What do we know about effective approaches to self-care ?

- What is the role of ‘community’ in relation to burnout ? How might we pro-actively get better at supporting each other ? What do we need community to be like for us ?

This webinar was recorded on Friday 23rd February 2024

Minding Ourselves

Those of us involved in Climate Action (activists, scientists, educators, sustainability consultants, etc) all know people who have suffered health issues, as a direct result of their involvement in the field. Burnout and damaged immune systems are common amongst people when there is a big gap between what we aspire for in the world and the realities that we encounter. Even more so, if we feel that anything we are doing is making little difference and even more so again, if we feel alone and unable to talk well about things we are thinking about.

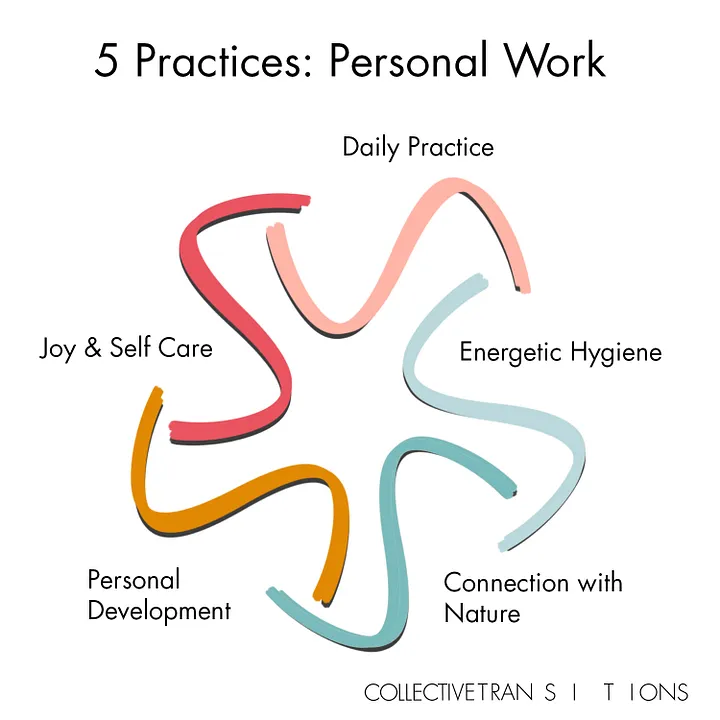

There are obviously lots of resources regarding how anyone can look after themselves (i.e. eat well, sleep well, exercise, mindfulness, be creative, etc). We particularly liked (and found useful) this framework / approach from our webinar guest, Luea Ritter – Dedication to our wellspring. 5 personal practices as hosts… | by Luea Ritter | Collective Transitions

There is a risk that the way we think about wellbeing can be over-individualised (i.e. we can pretend it is all about how individuals look after themselves). Managers, organisers and communities should have a ‘duty of care’ towards the people they are involving in climate action. We think this is a neglected area.

A lot of what makes the biggest difference in helping us mind ourselves is about how we are connected in and as communities. Are people left alone with their stresses and concerns? Do we have ‘islands of sanity’ where people can talk healthily about their fears, concerns and unfulfilled aspirations? Are we all just too busy for this stuff? One of the biggest factors that will dictate how successful we are in the work of climate action is how well we care for each other.

Other Useful Resources

Inner Development Goals Toolkit – idg.tools – a very flexible range of tools helping us to make links between inner and outer development and wellbeing

WHO DO YOU CHOOSE TO BE? AN INVITATION TO THE NOBILITY OF LEADERSHIP (margaretwheatley.com) – exploring the role of leaders and leadership in challenging times

The Enneagram – How It Can Improve Wellbeing The Enneagram – How it Can Improve Wellbeing – recognising that different personality types are likely to be vulnerable in different ways. Awareness of where one is likely to be ‘at risk’ is extremely helpful!

Engaging Our Wider Communities

How do place-based centres best engage and connect with our wider communities, especially those who have been marginalised?

Nicola Winters, from Sonairte – the National Ecology Centre, facilitates a discussion around some of the challenges of and solutions to engaging with people from all backgrounds. Sharing their experiences are Stephen Hayden from Ballymun City Farm, Davie Philip from Community Climate Coaches, Áine Bird from Burren Beo Trust and Amani Kamal – originally from Palestine and now working with Sonairte.

This webinar was recorded on Friday 16th February 2024

Barriers to Social Inclusion

Introduction

This article looks at how place-based centres experience and approach accessibility and inclusivity issues.

These issues were explored in depth at a day-long facilitated discussion at Carraig Dúlra with a broad range of participants including people that work with marginalised communities, leaders that have set-up support networks for their own group’s needs, people that run place-based initiatives and those that are trying to set one up. A safe space was created so that opinions and experiences could be shared openly. These opinions are expressed here.

Following the discussions, the partners in the project examined whether and how they approach the barriers to inclusion and their approaches are also presented here.

General

It is broadly acknowledged that environmental and social movements started to diverge from each other in the 1970s. Some have theorised that this was because environmentalism started to be the domain of scientists, requiring access to third level education while social justice could be led from working class or marginal groups self-organising.

Many government policies and incentives regarding climate change tend to focus on measurable but highly technical carbon-reduction targets and the use of financial incentives to take action. This approach has led to the messaging that putting solar panels on your house and buying an electric car are the solution to environmental issues, but this kind of consumer based action is only available to those with the resources to apply for the grants and pay for the work. This leads to a feeling that making a positive change is not possible for those with limited resources, disenfranchising many people in the process.

Climate Justice has begun to bridge the understanding of social justice issues with a more systemic and structural understanding of issues that have the same root causes and impact the same people.

One area of Climate Action that has been bridging the historical divide is that of nature-based solutions: community gardens, biodiversity supports, citizen science and more.

A sense of connection to nature and other people is a strong motivation for taking action on climate change. Research shows that if we have a relationship to nature then we are more invested in caring for it and prioritising conditions for it to flourish and regenerate. Place-based learning centres can offer that experience of nature connection and community. However, there is a huge diversity of barriers to accessing the nature and community connection offered by place-based centres with often unintentional and built-in levels of accessibility.

Research paper: Country-level factors in a failing relationship with nature: Nature connectedness as a key metric for a sustainable future.

Áine Bird from the Burren Beo Trust, who contributes to the webinar ‘Engaging our Wider Communities’ looks at What is the significance of place? Why should we care? in section 2.2, page 13.

Promotion and Sense of Welcome

How centres are presented to the public is very impactful in terms of accessibility and participation or engagement. What may be appealing to one group of people may be off-putting to another. For example, promoting your organic café may appeal to a middle-class audience but be perceived as elitist and expensive to those without a disposable income. Understanding the needs of various groups of people and making the centre’s offerings relevant to those groups is important. It takes significant time and resources to carry out this work and this can end up a low priority when capacity is already an issue.

What approaches do centres take when promoting their activities to as wide an audience as possible?

Carraig Dúlra Permaculture Farm promotes their work through local SICAP (Social Inclusion and Community Activation Programme) and PPNs (Public Participation Networks). They put specific effort into making the language accessible and use a lot of images to show what they are doing together. They avoid preaching or explaining the “why” in their communications. However, they recognise that some people may not ever want to visit the demonstration site at Carraig Dúlra and so address issues of accessibility through their outreach work in developing nature-friendly, community growing spaces in disadvantaged and marginal communities.

Sonairte – the National Ecology Centre is open to the public and entry to the courtyard, playground, Eco Shop, 2nd hand shop, Café, Bee Museum and Long Hall and many public events in these areas is free, with a small charge of €3 per adult and €1 per child for admission into the gardens and Nature Trail making it financially accessible to over 4,700 visitors in 2023. They have a strong social media presence on Twitter/X, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn reaching a broad range of people.

Some questions and comments that came up during discussions exploring how to be more inclusive of marginalised groups

Can we serve a diverse range of people with the same facilities?

While we should listen to those disadvantaged communities about the challenges they face, we don’t necessarily have the language or understanding to effectively communicate with people from disadvantaged backgrounds without specialists or diversity training. Poor communication has the potential to be more disconnecting despite the intentions behind it.

As we are part of a diverse, other-than-human world, diversity in the human ecosystem is very important for understanding and creating solutions to shared challenges. The knowledge, wisdom and time of marginalised people need to be valued and not exploited for co-creation opportunities. For example, members of the Travelling community have an ancient cultural understanding and stories of living close to the natural world. They also have many years as workers in what is now called repurposing or the circular economy and have skills in this area. This is being developed by one Traveller run social enterprise called Bounce Back Recycling, in county Galway who describe themselves as “an environmentally conscious organisation, delivering a recycling service which diverts mattresses & bulky waste from landfill or incineration.”

Many place-based environmental focused centres are started by middle class people who have access to resources. This can result in the tensions between people’s good intentions and the exclusion of people from more disadvantaged groups. It’s essential to address privilege and tackle issues of guilt and shame, ensuring that everyone, including those from middle-class backgrounds, confront their biases and actively work towards inclusivity.

The “green” movement has two core messages – reducing environmental impact while improving the quality of life. Disadvantaged communities in Ireland, and in the Global South, cause the least environmental impact and have the least resources to engage in improvements to their quality of life or meeting basic needs such as housing, meaningful work or activity if a disability excludes them from the world of work.

Sonairte has, since its inception, had a strong focus on engaging with marginalised groups. They have organised several Ukrainian events, Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth funding for events with asylum seekers, World Wise Global Schools Youth for Change funding (where asylum seekers are engaged as trainers) and they have welcomed several volunteers from direct provision through EU Voice and Connecting Cultures. They also participate in the Sanctuary in Nature initiative. Their CCAP Strand 2 project Climate Action Local Food has an advisory board which comprises 58% males and 42% females, with 50% representing social inclusion target groups.

Mental Health

Wild spaces and a supportive community are vital for mental health. Humans are part of the ecosystem and there is a call to remember, we are of the land. Multiple overlapping causes have resulted in a Global North or Western modern society that is more individualistic, siloed and disconnected from nature, with a consequent effect on our collective mental health. Discussions explored how we take action that impacts the way we have constructed society? Place based centres are seen as possible pockets of connection and community, countering the silos and fragmentation, where there is the opportunity to create space, time and context. Healing the ecological divide from nature, social divisions from each other and spiritual divide from the larger than human world or connection to our essential self, is cited as a motivation or vision of many place based centres.

Carraig Dúlra engaged with their local HSE Social Prescriber to provide opportunities for nature connection to those seek or need it. They also host various disability groups who engage in social farming activities.

Cloughjordan Ecovillage has a core focus on building a strong community of members and residents that is supportive, provides access to nourishing food and to natural spaces for nature connection. The community support is both structural (developing engagement processes that allow all voices to be heard, community communication structures) and non-structural (developing a culture of looking out for one another). Anecdotally, it is proving very supportive for some people with mental health issues and could be built upon to ensure this is experienced by everyone in the community.

Physical Disabilities/ Mobility Impairment

Natural spaces can be challenging for those with physical disabilities or mobility difficulties. Some things that facilitate people with mobility issues, such as clear wide paving and interpretive signage, can have the effect of diminishing the level of connection for those that desire a more immersive experience.

This was taken into consideration for some areas of the Cloughjordan Ecovillage which had many elements of co-design by the community. The village considered the needs of all ages and chose to focus on pedestrians and cyclists rather than motorised vehicles. Cloughjordan Community Farm within the Ecovillage is developing a biodiversity area, Cuan Beo, that is fully accessible with level access floors, raised planting areas and a wheelchair accessible compost toilet. There is also an accessible sensory garden that is aimed at stimulating all of the senses through nature.

Sonairte has worked hard to improve disability access to the centre. They recently obtained funding from Meath County Council via a Community Recognition fund to improve site access for people with mobility or visual impairment including new parking spaces, ramps and a new disabled access bathroom. The garden is now partly accessible for wheelchair users, with limited access via flat paths to the start of the Nature Trail. However the rest of the Nature Trail is hilly and inaccessible by wheel chair. In order to allow those who cannot physically access all parts Sonairte carried out a Heritage Council funded project “Getting to know you” which enables users to scan a QR code which will give a virtual tour of the site.

Sitting on a hill on scrub land with lots of uneven and rocky areas, Carraig Dúlra is not accessible for people with moderate to severe mobility issues. This has always been a concern for founders and only partially addressed through improvements to paths. They offer very customised solutions for individuals including wheelchair users but much of the site is not accessible to this cohort. The remote and quiet nature of the location have been cited as very helpful on a sensory calming level for some visitors, participants and volunteers with Autism Spectrum Disorders.

As part of this project we gathered a broad range of information from 24 place-based centres around Ireland. 10% report that their site is not accessible to those with mobility based disabilities, 55% say that it is partially accessible and 35% say that it is mostly or fully accessible.

Financial Limitations

Fairshare is a challenge. The ability to access place-based centres is often linked to disposable income – the centres cost money to run and there is often a cost to participate in courses or events. Even if an event is free there are costs associated with getting there or childcare. Better supports for people with limited financial means is needed.

Carraig Dúlra takes a financial ‘needs blind’ approach – a policy of not letting finance be a barrier. Where possible they offer grant aid, bursaries or other forms of exchange for course places. Participants on their Permaculture Design Certificate course can avail of Training Grants where eligible. They host meitheals, hold open days and bring in groups where people can engage with the land, connect with one another and learn new skills at no cost.

At Sonairte they strongly believe that access to safe, healthy, biodiversity-friendly food and access to nature must be accessible for all and that a Just Transition is imperative. For this reason they keep their prices low – many items in their Eco Shop and cafe are cheaper than in supermarkets, everything in their second hand shop is 2 euro. Entry to the centre is open to the public and most areas free, entry to the garden and trail is low cost – 3 euro per adult 1 euro per child. They provide free courses and events whenever possible, for example Biodiversity Week funded by the IEN and Heritage Council Heritage Week.

Cloughjordan ecovillage does not charge for entry and the walking trail, gardens and forest is open to the public all year round. In addition they host free events as part of Biodiversity week, Féile na nÚll (Apple Festival) and weekend tours.

Transport

Many place-based centres are in rural areas and getting there is often easiest with access to private transport and this can be a barrier for many people.

Cloughjordan Ecovillage chose its location because it is on a train line between Dublin and Limerick. However, the service is limited and under constant threat of closure despite an active campaign to keep the line open and increase the frequency of trains. There is also a limited local bus service connecting Cloughjordan to local towns. Where possible, they offer a discount to people attending events who travel by train, though with a limited service the timings often don’t suit.

Despite an ongoing campaign, Sonairte is still not accessible by public transport. It is a 10 minute walk to the nearest bus stop and train station along a road with an 80km/h speed limit with no footpaths or street lights. This can be dangerous for staff and visitors, especially in winter. They have repeatedly lobbied the National Transport Authority and local council to extend the bus routes to pass Sonairte but have not yet been successful.

Carraig Dúlra is not located on public transport routes, the nearest train or bus is 2-6km away. While some people have walked or cycled this distance, they regularly offer pick ups and help participants to organise lift shares.

Capacity to do Needs Assessment

Capacity is an issue for many place-based centres (see Can We Make a Living? in the Insights Section) and the capacity to evaluate the needs of different groups and overcome the barriers they face can be a struggle. Questions like “Who do we centre in our activities?”, “Who or what are we in service to?” and “Who or what are our priorities?” can be uncomfortable and challenging to answer but are necessary and helpful for reflection and evaluation of levels of inclusion or exclusion in place-based learning centres.

Social Inclusion Resources

Pobal Guide for inclusive community engagement in local planning and decision making.

The Importance of Celebrations to Communities

Celebration is vital to Community

Celebrations are a great way to bring people together. They give everyone an opportunity to take a step back from the minutiae of everyday life and express appreciation and gratitude on any occasion, small or momentous. Celebrations can act as a reset, reminding us all that we are a part of something bigger than ourselves. Planning the celebration can be a positive experience – allowing the desires and creativity of the community to come together to form a whole greater than the sum of its parts.

The Dragon Dreaming Institute, which describes itself as an institute to foster co-creative project design for social innovation, has a model of four stages of realising a project – dreaming, planning, doing and celebrating. They “strongly suggest that 25 percent of the cost and energy used in all projects should involve Celebrating!”

Barbara Ehrenreich in her book Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy describes group events which involve music, movement, costumes as being central to the cohesiveness of communities. Tribal cultures have ecstatic rituals and anthropological thought is that this practice was widespread, despite variation in ritual and mythology, until it was considered subversive, dangerous and “savage” by colonising authorities and suppressed.

She speculates that the desire to express collective joy has biological and evolutionary roots in protecting the community from predators: “Taken individually, humans are fragile, vulnerable, clawless creatures, but banded together through rhythm and enlarged through the artifice of masks and sticks, the group can feel – and perhaps appear – to be formidable as any non-human beast. When we speak of transcendent experience in terms of feeling part of something larger than ourselves, it may be this many-headed pseudo creature that we unconsciously evoke”

The biological urge for collective ecstatic experience cannot be easily suppressed, so western culture has shifted the focus to spectacle – concerts, football matches, parades – where the collective experience is directed externally, watching skilled professionals perform, allowing for a taste of the collective ecstasy, satisfying the need, without being a part of it. Festivals and Raves are two places where collective joy can still be fully experienced, though stripped of much of the ritual and mythology.

Reasons to Celebrate

Generally, there is a cause for every celebration – the completion of a project, a personal or collective milestone or to mark the seasons. Often it is the act of coming together to celebrate that is more important than the stated reason for it.

Camphill Communities is a worldwide social initiative that creates communities designed to include people with and without intellectual disabilities. Celebration and creativity are integral to their ethos. Gladys from Camphill Ireland says “Everyone had a birthday party that celebrated who they were within the context of their place in the community. Parties make people feel special and part of something bigger than themselves, but at an accessible scale.”

Case Study – Féile na nÚll – Apple Festivals as a Tool for Community Cohesion, Cloughjordan Ecovillage

Introduction

Cloughjordan Ecovillage holds Féile na nÚll every year on the Saturday closest to the Autumn Equinox, when apples are ready to be harvested. The edible landscape in Cloughjordan Ecovillage includes hundreds of native apple trees and these form the foundation of the celebration. Members of the community bring ideas about art projects, performances or workshops to share their knowledge and creativity.

Apples and Community

As the trees grow, so does the community that celebrates them. The act of coming together to plant, care for and harvest from the trees engages the community in a very fulfilling way. The trees bring joy from the early buds and blossoms signifying spring, to the heavily laden branches in summer and the ripe aromas as the fruit starts to fall. The changing sensory experience of moving among the trees brings people and nature together. At harvest time, the community celebrates abundance, working together and preparing for winter.

Apples and Biodiversity

Apple trees support many species of insects, birds, bats, mosses and lichens. Windfallen fruit is a vital source of food in autumn and winter for a whole range of wildlife, so leaving some fruit where it falls is essential.

Apples as a Commodity

Global apple production is a valuable commodity with China being by far the largest producer. The expectation of a year-round supply of perfect apples at low cost has resulted in large, intensive farms using low cost and often exploitative labour, massive refrigerated storage facilities, long-distance transport, biodiversity loss, extensive pesticide use and fewer varieties available.

At a local level we can change our approach to apple production – returning it to small scale, local varieties, seasonal availability and imperfect fruit. Community orchards can produce nutritional fruit while increasing biodiversity, increasing our connection with nature and promoting local food security.

https://pollinators.ie/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/AIPP-Farmland-Orchards-2023-WEB.pdf

Link to the How-to Guide for Traditional Orchards for Fruit Trees and Pollinators on the Farm from the All Ireland Pollinator Plan.

Apple Festivals – How-to

Organising the festival requires work and creativity but brings great value to the community. We use the facilities and spaces available to us so costs are kept low and there is no charge to visitors. There are many apple-based activities that can be included and these can be replicated by any community with access to even a few apple trees.

Apple identification and tastings

Cloughjordan ecovillage has over 70 heritage varieties and 600 apple trees around the site including varieties for eating, cooking and cider-making. They are clustered in orchards, they line the pathways as part of the edible landscaping and there is an Apple Tree Avenue along one edge of the allotments where over 70 varieties are planted are in two rows creating a tunnel through them. All of the trees came from Seedsavers in Co. Clare.

The knowledge about the varieties and their qualities is shared at the apple festival. The fruit, with their often-curious names, are available to sample and this tends to really engage the public. We often learn something new from someone who has some personal or historical lore to share. Knowledge can be shared about where to source heritage varieties as well as how to care for and propagate them.

Juicing

Apple juicing is the most engaging aspect of Féile na nÚll. People bring boxes and barrows of apples from around the ecovillage (with over 600 apple trees, people are encouraged to collect the apples around the site), their gardens and hedgerows for juicing.

Juicing is a great way to use, store and add value to an apple harvest. Any kind of apples can be juiced to produce an array of flavours. Juicing can use windfalls, bruised or damaged fruit or apples that do not store well. Tasting the juice from certain apples or combinations of apples is a great way to get people involved and learn more about varieties.

Juicing apples has two stages – crushing and pressing. The apples need to be crushed before they are pressed to maximise juice extraction. Commercial electric crushers can be bought that process the apples efficiently. Pedal powered crushers can be home made and are a great way to engage children and adults. Presses can be commercially bought or home made and can be any size.

Due to the risks associated with the spinning blades of the crusher and the forces exerted by the press, the machinery is operated solely by a small number of competent people. However, there are tasks (such as loading apples into the hopper of the crusher or packing the crushed apples to the frames for pressing) that the public can get involved with. A system needs to be put in place to allow the public to participate while being prevented from interfering with or operating machinery. Adequate competent people need to be on hand to manage the process safely. A full risk assessment and method statement should be drawn up.

The juicing tends to foster connections between people. Children and adults participate in collecting the apples. Discussions on the best type of apple and where they are located, often closely guarded secrets, give people a common point of interest. Tips and tricks on pasteurisation, freezing and storage of the juice are exchanged as well as cautionary tales of bottles fermenting and blowing their tops.

Fermenting

Apple juice can be fermented into cider. Different apples produce different flavours and qualities – some varieties of apple have been bred specifically for the qualities best suited to cider making, but any apples can be fermented. The cider can also be flavoured with other fruits and plants such as berries or herbs.

Apple juice contains naturally occurring yeasts and bacteria. In many cases, the naturally occurring yeast can ferment the sugars into alcohol in the absence of oxygen, and this process kills off the bacteria that would otherwise cause the juice to spoil. A certain level of acidity in the juice allows the yeast to get to work before the bacteria. That acidity can also make the finished cider quite dry. For sweeter juice, it is common to pasteurise the juice to kill off the naturally occurring yeast and bacteria, then add some wine yeast to control fermentation.

The cider can subsequently be turned into cider vinegar which has a multitude of uses – in food, for cleaning or for health benefits. Cider is exposed to the air and a vinegar “mother” is added. Commercial cider vinegar with the mother can be purchased in health food shops and can be used again and again (similar to kefir grains or a sourdough starter).

Specialists can be brought in to run an information session or workshop on fermenting apples or a peer learning group can be organised or develop organically. People can bring a sample of their cider from last year to taste, groups can emerge to share encouragement, fermenting experience, resources and buying power.

Apple Bake Competition

The Apple Bake competition is hugely popular and fun. Everyone is invited to bake an apple dish and there are categories for children and adults. The judging panel includes the winners from the previous year and representatives from the local Irish Countrywomen’s Association. Small prizes are donated by local businesses and after the prizegiving, all of the dishes are shared with the community. The competition is a firm favourite with people from other countries that relish the opportunity to showcase the ways that their culinary traditions include apples, fostering integration with new members of our community.

Jams, Jellies and Chutneys

Apples are high in pectin, the soluble fibre that makes jams, jellies and chutneys set. They also tend to contain the acid and some of the sugar required to set the pectin. Therefore, apples can be used as a base for jams, jellies and chutneys that can then be flavoured with ingredients that do not contain enough pectin to set on their own – this is a good use for some of the pulp that is left over from juicing. Sharing this kind of preserved food is a great way to build food resilience and foster community connections.

Other Elements

We also include a market of local food producers and crafts people, music and dancing, performances, talks and workshops.